Let's talk about AI and Copyright law

The district courts in California have weighed in on "fair use" of copyrighted material by generative AI and so far, the news isn't great for creatives

Two recent decisions from cases in California are the first shots fired in what will inevitably be a long war between creatives and the companies creating generative AI models.

There has been a lot of talk about what these two Summary Judgment decisions mean (I’ll explain what that is in a bit) and the decisions have been called big AI wins. They are and they aren’t. But either way we should pay attention to how the courts have started to weigh in on this issue.

My day job is as an intellectual property attorney. Full disclosure, my work has focused on patents in the biotech world, I haven’t handled many copyright issues in the ten plus years I’ve been practicing law. But I want to give you some of my thoughts into one of these cases, what I think may happen next, and what the plaintiffs should argue to win against the generative AI companies.

Civ Pro Primer

First, let’s briefly go to law school. I promise to make this as painless as I can, and maybe even a little fun. Skip this if you are a lawyer (unless you want to see what I messed up) or you just want to get to the case breakdowns.

There are two major branches to courts in the United States. There are state courts and there are federal courts. There is a bunch of law dealing with how these two court systems interact, but for our purposes just think of it this way: generally, federal courts deal with anything having to do with federal laws and with the Constitution (there are other reasons like class action lawsuits); and state courts that deal with everything else (criminal cases, traffic cases, divorces, etc etc). Because copyright law comes from both the U.S. Constitution and from the federal Copyright Act, the cases will almost exclusively be heard at the federal court level.

The federal court is split into three levels. There is the District Court, that’s the first tier and where any case will start. Then the Appellate Court and then the final court the Supreme Court.

Every state has at least one District Court and some states have a bunch. The District Court tier is important because these courts are focused on considering the facts in the case. OK … let’s pause here for a second because I remember that this sounded weird the first time I learned it.

Any court case is decided based on two major categories, the facts of the case and the law that applies to those facts. It’s easiest to think about criminal law when trying to understand this concept. If an alleged murderer is on trial, the prosecutor will say that Colonel Mustard used the wrench in the library to kill the victim. These are the alleged facts, I say alleged because the prosecution has to prove to the court that those are the real facts (you hear this called their burden of proof). In criminal cases this burden is high, they have to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt. (Burdens of proof is its own interesting topic but let’s not get too sidetracked.) In civil cases, all the cases that don’t involve a crime, the burden is lower, like just barely over 50/50 that its true. This is called the preponderance of the evidence, it just needs to be 51% certain. (I hear you out there my lawyer friends, you were supposed to skip this section … yes, there are some cases that require a higher burden of proof in civil cases but let’s not make this overly complicated.)

Then the law is applied, in this murder trial against Colonel Mustard, we apply the law that it is illegal (everywhere but Vegas) to kill someone (just kidding Vegas, I love you). We can get more technical here, like what that law says about someone’s intent when killing someone, but that isn’t necessary to get the concept.

Any trial is about determining the facts and then applying the law to those facts.

The lower District Courts called trial courts takes testimony from witnesses, considers evidence (like documents or pictures for example), and hears arguments to determine what the facts of the case are. The arbiter of what these facts are is either a trial court judge or jury.

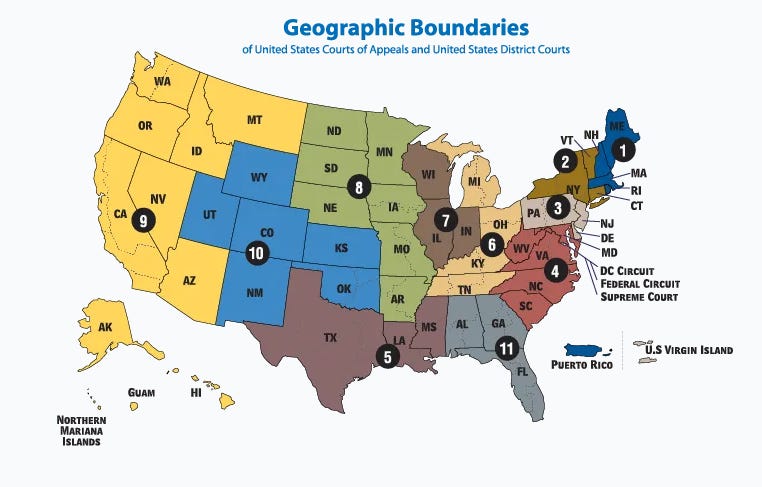

Next up from the trail court is the Appellate Court level. You’ll hear the news talking about the 4th Circuit court or my home circuit the 10th Circuit court. These circuits are based on geography.

These are the appellate courts who will hear some, not all, of the cases from the lower trial courts if one of the parties appeals the ruling.

Once the trial court has determined a specific fact it is tough for the other tiers of the federal court system (appellate courts or the Supreme Court) to disagree or to come up with their own decision on what the fact is or is not (they still do sometimes which I personally think is a big issue). In part, because these higher courts weren’t there in the room with the witnesses, or considering the primary evidence, to make a judgment about who or what to believe. They just read about what the evidence was or what the witnesses said. These courts are supposed to focus on whether the judge or jury made the right legal decision based on the facts of the case. Was the law applied correctly?

The final court, that only hears a handful of cases every year, is the Supreme Court.

Done. You made it. That took me months to learn in Civil Procedure in law school.

The Anthropic cases

The reason I gave you that little law school course is so you can appreciate and put into perspective what these two lower court rulings mean now and what the implications are for the future. I’m going to focus on the Anthropic case because I think it points the way forward for authors to win in other lawsuits, and potentially in this lawsuit on appeal.

Before telling you what the court decided in the Anthropic case, let’s fast forward to a totally plausible future.

The cases that have made decisions about generative AI and copyright law are federal district courts in California. These are the lowest federal courts. Here’s why that is important, other district courts could come up with different decisions based on very similar facts and applying the same law. It would have to be a different case, but it is possible that another set of authors could sue different AI companies, in different states. And don’t forget, the trial court decision can get appealed to the higher level court, in this case the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Now let’s say the 9th Circuit hears the cases against Anthropic and Meta and makes a decision. Then let’s consider the New York Times lawsuit against OpenAI (maker of ChatGPT) in New York and that gets appealed eventually. In that case it would be appealed to the 2nd Circuit. But it’s possible the 2nd Circuit court and the 9th Circuit court come up with different rulings (when have New Yorkers agreed with anything a Californian has to say?). That’s where the Supreme Court would step in. One of their favorite types of case are when two circuit courts disagree and they step in and make one final ruling (like the one ring) to rule them all. Once the Supreme Court has made a ruling the only court that can overturn or alter that ruling is the Supreme Court itself, which they aren’t supposed to do often (let’s not dive into that mess), or the U.S. Congress can make a new law. I guess there is a third way, the Constitution can get amended, but I honestly doubt that will ever happen again.

In other words, the story is far from over. Hopefully after your mini-law school course you can appreciate where we are in the lifespan of these cases. This is basically a prologue to what I suspect will be a long drawn out mess. In fact, this is only the first ruling in Anthropic, a trial is yet to come (more on that in a bit).

Bartz v. Anthropic

The authors (Andrea Bartz and the rest of the plaintiffs) class action lawsuit against Anthropic (maker of Claude) claims that their copyrighted material was infringed (stolen) when Anthropic used it both to train its Large Language Model (LLM) and to create its digital library. I’m far from an expert on LLMs and generative AI, but my understanding is that the LLM is like the engine powering the tool (like Claude or ChatGPT) and this engine has been fed zillions of words in zillions of books to teach the tool how to respond to questions or to create its own words strung together. The digital library at issue was Anthropic basically scanning these books and digitizing their words into a central library, that they’d then use to train their LLM.

To understand what the court ruled here we have to dive into copyright law and what “fair use” means.

Copyright law comes from both the Constitution (Article 1, section 8, clause 8, in case you are curious) and the Copyright Act of 1976.

Article 1 of the Constitution says that the U.S. Congress has the power:

To promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.

The Copyright Act says:

Copyright protection subsists, in accordance with this title, in original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device. Works of authorship include the following categories:

(1) literary works;

(2) musical works, including any accompanying words;

(3) dramatic works, including any accompanying music;

(4) pantomimes and choreographic works;

(5) pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works;

(6) motion pictures and other audiovisual works;

(7) sound recordings; and

(8) architectural works.

Bottom line, you write something or paint something or print a picture of something on a tangible medium (something that can be perceived by someone else, or reproduced) then you have the right to that work of authorship. Here’s where lawyers make their living, there are exceptions. One of the exceptions to this law is called the “fair use” limitation. It is also outlined in the Copyright Act:

[T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means … for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Basically, if you are a teacher and reproduce an author’s writing in a classroom, that would be a clear cut fair use of the copyrighted material. These four factors of what is and is not fair use are where the rubber meets the road, and where I think the judge in the Anthropic case made a pretty big error.

The ruling in Anthropic was based on something called a Summary Judgment motion. That is where one side says to the court that the case or part of the case should be decided before trial based purely on what the law and the “undisputed” facts of the case. I say undisputed because, remember one of the big jobs of the trial court is to determine what the facts are. But the court doesn’t need to look at facts that both sides of the case agree are facts, these are undisputed facts. Anthropic made their Summary Judgment motion saying that their use of the material from these authors fell under “fair use” and the case against them should be decided before a full trial.

The judge agreed with Anthropic in part and disagreed with Anthropic in part.

Anthropic said that they just used the copyrighted material that they had digitized into a central library to “train” their LLMs. They acquired these books in part from online pirated libraries, and from books that they claim they purchased. (They also claimed that they later purchased some of the books that they had downloaded from the pirate websites.) It also claimed that the central library they created would be used for “research” as well as to train their LLMs. The judge agreed with the authors that Anthropic used the books first to create its central library and then used the books to train the LLMs. Two separate uses.

Here’s what the judge said, when considering that first factor of the fair use limitation, that “the purpose and character of using copyrighted works to train LLMs to generate new text was quintessentially transformative.” The court then said that, “[l]ike any reader aspiring to be a writer, Anthropic’s LLMs trained upon works not to race ahead and replicate or supplant [the books]—but to turn a hard corner and create something different.” I think this was shockingly short sighted (we’ll get into it in a bit).

The court then said Anthropic could digitize any book it had purchased for its central library as a “mere format change” of something they rightfully owned. But then the court said that it would not make the same decision regarding the pirated copies that Anthropic acquired, and that even those books Anthropic first took from pirate websites but later purchased didn’t absolve them from being considered pirated.

In other words, the court said that because the books were “transformed” and that the LLMs were not trying to compete with authors, the training of the LLMs with purchased books would weigh for “fair use” under that first factor. And the creation of a digitized library was allowed if the book was first purchased under that first factor.

The judge then looked at the other factors, with regard to the second factor “nature of the copyrighted work” the court said it weighed against fair use because all the books contained expressive elements which is why they were chosen by Anthropic.

The next factor, the “amount and substantiality” of the copyrighted works that were used was considered. This factor looks at whether the amount of the work copied was reasonable when considering the reason they were copied. Here the judge said that because the copies were used to train the LLMs, this factor favored it being a fair use because the copying of the full books was reasonable to transform the works, and that there was no evidence that the works being copied were then presented in full to the public. Again, I think this was a mistake by the judge (but I’ll get into that in a minute).

The last factor is whether the copying has an impact on the market value of the copyrighted work. This is where the court made some bigger errors, he ruled that LLMs did not and would not replace demand for the original copies of the author’s work. I think the author’s made a mistake arguing that there would be a “market dilution” that LLMs would flood the market with new and competing books. The judge disagreed with them and said it was no different than “training schoolchildren to write well would result in an explosion of competing works,” which is “not the kind of competitive or creative displacement that concerns the Copyright Act.” Rather than market dilution the authors should have argued that this new technology would directly compete with the original works. (I’ll tell you what I mean in the next section.)

Then the court discussed the “licensing” market for books being licensed “for the narrow purpose of training LLMs,” which the authors argued was being destroyed by Anthropic’s use. This is the author’s strongest argument, in my opinion. The judge brushed it aside and said that the Copyright Act does not entitle authors to this market because the LLMs are transforming their original works to such a high degree.

In short, the court held that the factors under fair use weighed in favor of the use of the purchased copyrighted books to train the LLMs and to build the central library was a permissible and was not an infringement of the copyrights. The judge emphasized that “[t]he technology at issue was among the most transformative many of us will see in our lifetime.” The issue regarding the pirated works will go to trial to determine the damages for that copyright infringement.

What does this mean?

The judge in the Anthropic case focused much of the decision on his fundamental misunderstanding of the transformative nature of LLMs being fed copyrighted material.

He just looked at what was in front of him, and this may be an error in how the case was presented by the authors, or maybe because the record wasn’t fully developed yet, I haven’t looked deeply into what they argued specifically. What was in front of him was just that books were scanned into digital form and fed to the LLM to train it. Period. There was no evidence that the LLM would then spit out an exact reproduction of the book and so he stopped his analysis there and determined it was transformative fair use.

I think we can all agree that it was transformative if that is where this all stops. But it isn’t where it stops. The books are fed to the LLM as a first step. They learn about sentences and structure and how to write dialogue generally. But LLMs keep getting stronger and stronger. Let’s think just a little bit about what’s coming maybe in weeks or months but definitely in the next few years. This is something the judge failed to do. These LLMs will not only be able to replicate an author’s sentence structure, diction, dialogue, paragraph length, chapter length, but will be able to reproduce their style and tone and theme.

What’s to say that someday a user can’t say to an AI tool, “I want to read a new Stephen King book about killer bunnies in a New England town in the 1960s and I want it to be less than 300 pages long and I want a happy ending.” Pop. Out comes a book that sounds and feels like King’s writing. This judge and proponents of generative AI creative writing would say, “yeah … what’s the problem with that?” In fact, the judge said that training LLMs was like training “schoolchildren” how to write, so how could the Copyright Act protect from those new authors. Well its not the same at all. It is a machine that may someday be able to produce a 300 page book in any author’s style in seconds. That is inhuman. That is not something that the “fair use” limitation on copyright law was meant to protect.

If some person were to only read Cormac McCarthy for their whole life and then write a book in his style, that is totally different. It might be good. It might be terrible. We might even love the book. Because it was an act of human creativity. Every good artist steals. Every good writer steals. But then we run that style and impulse and inspiration through our own human experience and our human creativity with the craft. That is art. What is it if generative AI someday does this? It’s a photocopy. A facsimile on steroids. Until we are talking about true Artificial General Intelligence, I, Robot type intelligence, there is no soul behind what AI does. And it WILL harm the actual human artists toiling away to create art. How can it not? Copyright is meant to protect an artist’s exclusive right to their writings. Looking at what AI does though the same lens as what another human writer could do is a mistake. AI can do things with a speed and precision that humans can’t do. This might be something that Congress will need to clarify in a law.

I’ve recently heard of an AI tool (I won’t link to it out of principle) that you can ask to talk to you like any character from any book. Who knows if it is any good, but what if it does get good? Really good. Human authors can not compete with that.

Let’s look at the fair use factors. The judge said that just feeding books to the LLM to train it wasn’t competing with the original authors. What? That is short sighted. Of course it’s competing and as time passes that competition will be brutal. To me, this is like saying someone who films a movie in the theater isn’t infringing a copyright until they decide to sell that copy on a street corner. Huh? Wrong. What Anthropic and these other companies are doing is way worse than that kind of piracy. And yet that bootlegger could get hit with huge federal fines for just filming the movie on his phone. The production company that made the movie will lose maybe a few hundred dollars of revenue to the street corner pirate, maybe a few thousand if the bootlegger really hustles. LLMs are poised to crush entire creative markets. How on earth is that where the analysis stopped in this case? The entire reason they are feeding these books into the LLMs is so someday soon they can write just like a human author. That is obvious. They aren’t just doing this in a lab to see how smart they can make an LLM sound. It is a tool that can be used to directly compete with the original copyright holders.

What do we do?

Here’s where I think there might be a silver lining and a way forward. First the silver lining. As these generative AIs keep getting better and better it will become more and more clear that they are in fact competing directly with the authors who they learned from. The record will continue to develop. It will be more and more clear that the new AI Stephen King will sell it’s services. That cuts against the first “fair use” factor as a commercial purpose. It will have learned by reading copyrighted books and it will have learned from King’s entire bibliography. That’s the second and third factors against AI’s fair use. Then it will be obvious that the AI Stephen King has taken revenue away from the horror genre GOAT. That’s the fourth factor.

The plaintiff authors in Anthropic will eventually appeal this Summary Judgment, but what they need to hammer home is how the trial court judge misunderstood the supposed “transformation” of the copyrighted material. That LLMs are being trained in order to directly compete with these authors. This isn’t happening in a vacuum. The plaintiffs also need to emphasize the destruction of the licensing market by the trial court’s decision.

That is the way forward.

Think of it this way, would it have been enough for Denis Villeneuve to simply buy a copy of the Dune books before making his movies? Nope. He had to buy the movie rights, the license. But how is this possible? Villeneuve is creating something absolutely transformed from the books, some argue (don’t yell at me) even better than the books. But he still has to get the license from Frank Herbert’s estate. Dune is still protected by copyright. Because of the Copyright Term Extension Act it will be protected until 2060. How is this use of copyrighted material by AI any different? Author’s should have the absolute right to sell their books under license to companies training LLMs and more importantly have the option not to sell them the books, art, or music. Feeding the LLMs is transformative and even their output is transformative but that doesn’t constitute fair use because, as I’ve argued, it does compete and it will hurt the market for the copyright holders. Author’s should have every right to opt out.

I haven’t talked about the Meta case (mostly because the judge just ruled that the plaintiffs had made the wrong arguments with insufficient evidence) but something the judge said there should also give us some hope:

“No matter how transformative LLM training may be, it’s hard to imagine that it can be fair use to use copyrighted books to develop a tool to make billions or trillions of dollars while enabling the creation of a potentially endless stream of competing works that could significantly harm the market for those books.”

My hope is that is where this will all end up. Authors and artists will have a choice to get paid a licensing fee for the use of their work to train LLMs. The explosion of AI is gaining speed and is inevitable. It isn’t all bad. (I’m not touching on the environmental impact of these AI companies, which is another topic entirely and is universally horrible.) But what AI shouldn’t do is hurt future generations by depriving them of future creative works made by other humans. It shouldn’t replace the creative process. It shouldn’t be necessary to make a new fake sticker for book covers saying “Made by Human.”

When we look back at past civilizations one of the things we look to in order to understand who they were as a people is their art. What happens if human artists become a fringe group. What if only the most crazy passionate people write and make art for the pure joy of creation with no hope to make it their career? What if most “art” is done by prompt? What will that say about us?